Albania, Off-Season: A Country Opening Up, Still Carrying Its Past

I’ve just returned from a short trip to Albania, and this is not a travel guide. It’s my set of impressions of a country that is beautiful, complex, and still negotiating the long shadow of its past.

Albania doesn’t yet sit comfortably on the mainstream European tourist circuit, though it clearly wants to. It’s a Balkan country that was once deeply isolated under a particularly hard-line communist regime, and is now, quite visibly, opening itself up, sometimes thoughtfully, sometimes chaotically.

Arrival and First Impressions

The immigration officers at the airport were, predictably, a little gruff. Nothing dramatic, just the usual mild hostility that seems to come as part of the global immigration experience. Our pre-booked taxi, on the other hand, was punctual and driven by a genuinely warm and helpful man; an early reminder that first impressions are rarely uniform.

We were in Albania for only four days and chose to spend most of that time in the south, based in Sarandë on the Albanian Riviera. We travelled in December, firmly off-season. That choice shaped the entire experience.

The weather was mixed: some rain early on, followed by two glorious days of winter sunshine. It never became truly cold, light jacket weather at worst. The Adriatic Sea, though, was unmistakably cold. Swimmable if you’re brave; pleasant only if cold-water immersion is your thing.

Sarandë: A Resort Town Asleep

Sarandë is a classic beach resort town; hotels, apartment blocks, promenades, all built for crowds that simply weren’t there. In December, most restaurants and hotels were closed. The town felt dormant, almost hollow, despite the density of infrastructure.

Our accommodation was a sea-facing villa that was genuinely lovely. But all pools were closed for winter, a reminder that this is a town built around a very narrow seasonal window.

The promenade, though, was a highlight: a long, gentle walk along the bay, boats tethered and mothballed for winter, cafés intermittently open. It’s easy to imagine how lively this stretch must be in summer and equally easy to wonder how it copes with the volume.

Food, for a vegetarian, was challenging. Albania is heavily meat and seafood-based. The vegetarian menu is essentially pizza, pasta, fries, and repetition. We ended up cooking many of our evening meals ourselves, partly for nutrition, partly for sanity.

Practicalities: Money, Movement, and Minor Panic

The local currency is the Lek, though euros are widely accepted. ATMs charge steep fees, often €6–7 per withdrawal (so withdrawing larger sums makes sense). Most restaurants and supermarkets take cards; taxis and smaller places often don’t.

We had a brief ATM scare when one machine failed to dispense cash after debiting the account. Thankfully, this turned out to be a known issue and resolved quickly, but it’s worth being prepared.

Walking Upwards: Views and Solitude

One afternoon we walked from Sarandë up to the Lukersi Castle on a hilltop that overlooks the bay. It’s a four-kilometre climb from the centre of Sarandë, about an hour each way. Entirely doable, moderately tiring, and completely deserted. The views were worth it. In peak season, I imagine cafés and crowds. In winter, it was just us, the bay, and silence.

Butrint: Layers of History

On the second day we took a bus to Butrint, an ancient Roman settlement about 45 minutes away. The bus cost 200 lek and was easy enough. Busses depart every hour and the staff were very friendly. I saw a live turkey being carried in a plastic sack for the first time in my life!

Butrint is quietly impressive with ruins layered with Roman, Byzantine, and later influences. A small amphitheatre, winding paths, and a hilltop castle with a modest museum of excavated artefacts. You don’t need more than an hour or two, but it’s well worth the trip.

Albania Explained by a Guide

The most illuminating day was a minivan tour inland with a local guide. Albania makes far more sense once someone explains it to you.

The flag—red with a black double-headed eagle—symbolises sacrifice and freedom. It’s striking, and oddly fitting.

Albania has been ruled by Romans, Byzantines, Ottomans, and finally itself—briefly. Post-WWII communism here was severe: religion banned, private property abolished, total isolation enforced. Albania was once described as the North Korea of Europe.

What struck me most was not just the brutality, but the continuity. Many of today’s political and economic elites are descendants of communist leaders. Inequality is stark. Average wages hover around €400–500 per month; in some villages, €100–150. Meanwhile, coastal property prices rival parts of southern Europe.

Depopulation is everywhere. Albania’s population has fallen from around 3.5 million to closer to 1.5 million. Villages are hollowed out. Migration to Italy, Greece, Germany, the UK (more recently) is normalised. One child stays back to care for ageing parents; the rest leave.

Roads, Memorials, and Disorderly Growth

Roads are better than expected, though driving remains… interpretive. Roadside memorials are everywhere. These are small shrines marking fatal accidents. Dangerous driving was apparently rampant until recently; increased tourism has forced stricter policing.

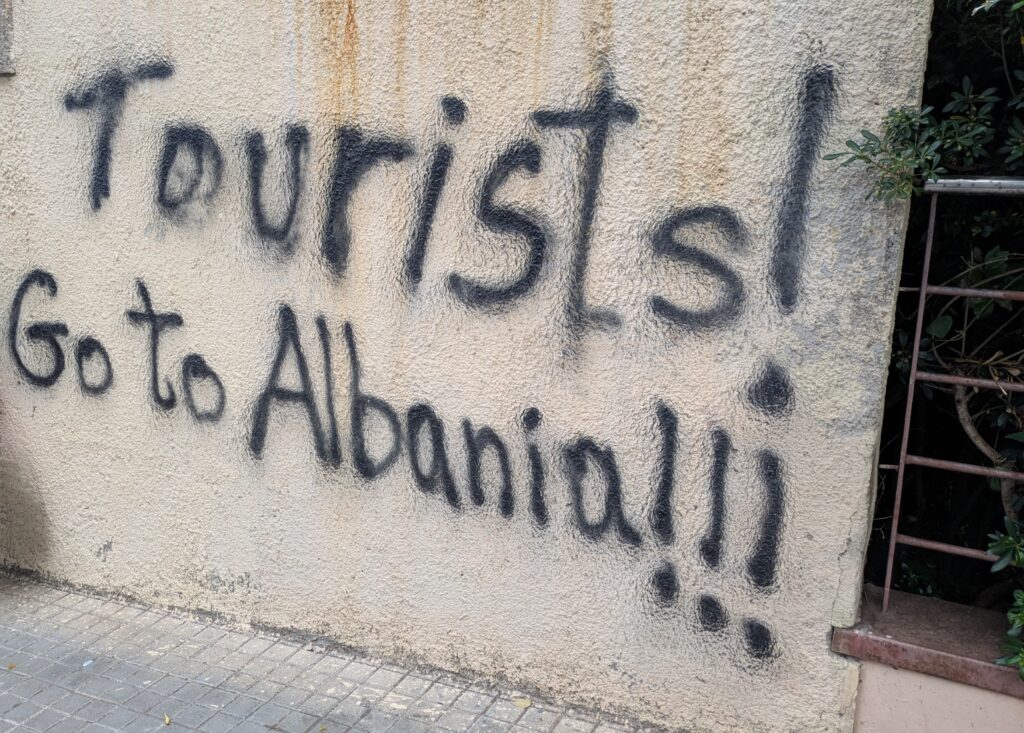

Post-communism brought freedom coupled with chaos. Unregulated construction is visible everywhere, especially in Sarandë: hotels and apartments built without planning, parking, or infrastructure. It’s hard not to wonder how the town copes in peak summer.

Tourism has inflated prices and strained resources, especially water. Many resorts rely on tanker deliveries from mountain springs. Supermarkets were noticeably expensive. Our modest shops costed £20–25. For locals on Albanian wages, this is not trivial. However, eating out is still relatively inexpensive. A pizza or pasta meal for 3 people would cost £20-25.

Inland Beauty: Blue Eye, Gjirokastër, and Thermal Baths

We visited the Blue Eye, a surreal, turquoise natural spring. The water is crystalline, the air clean, the walk peaceful. One of the most striking natural sites I’ve seen.

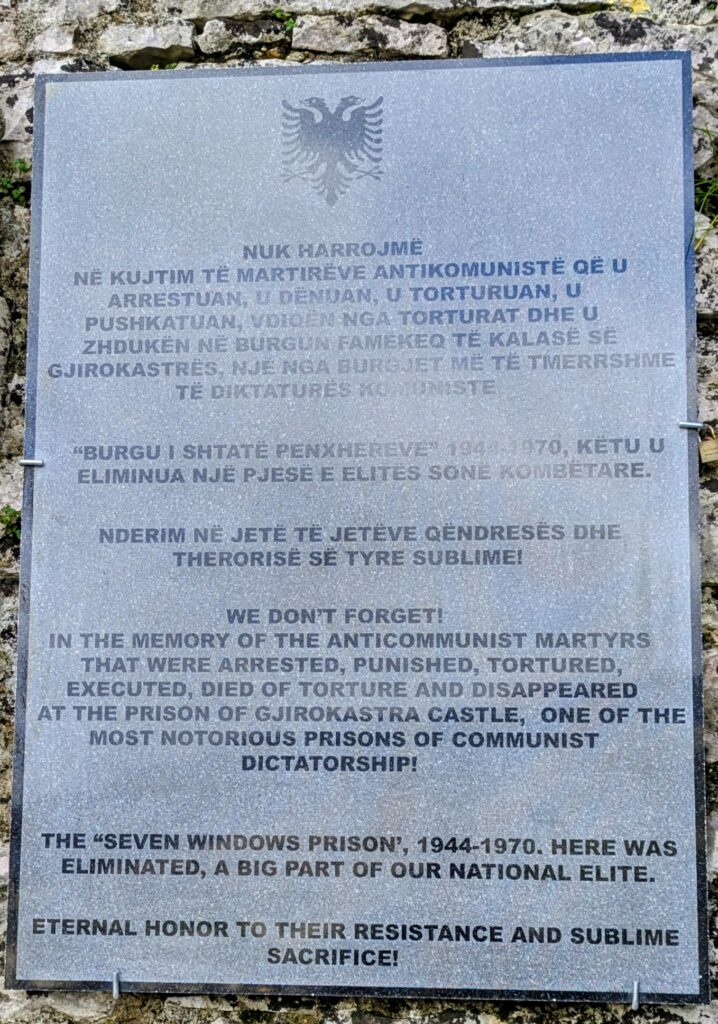

From there we went to Gjirokastër, an Ottoman hill town dominated by a castle later used as a communist prison. Inside the fortress: tanks, artillery, and reminders of more recent violence. Outside: charming stone streets, heavily tourist-oriented, but undeniably atmospheric.

A detour to thermal baths near Përmet was unexpectedly delightful. We had a great time in the outdoor pools fed by warm springs, surrounded by mountains. Clearly another area poised for development.

Berat, Tirana, and Confronting History

On the final day we detoured to Berat, Albania’s wine region. White stone houses stacked along a river valley, old bridges, and interestingly, the first real traffic we’d seen. Berat felt alive in a way Sarandë didn’t.

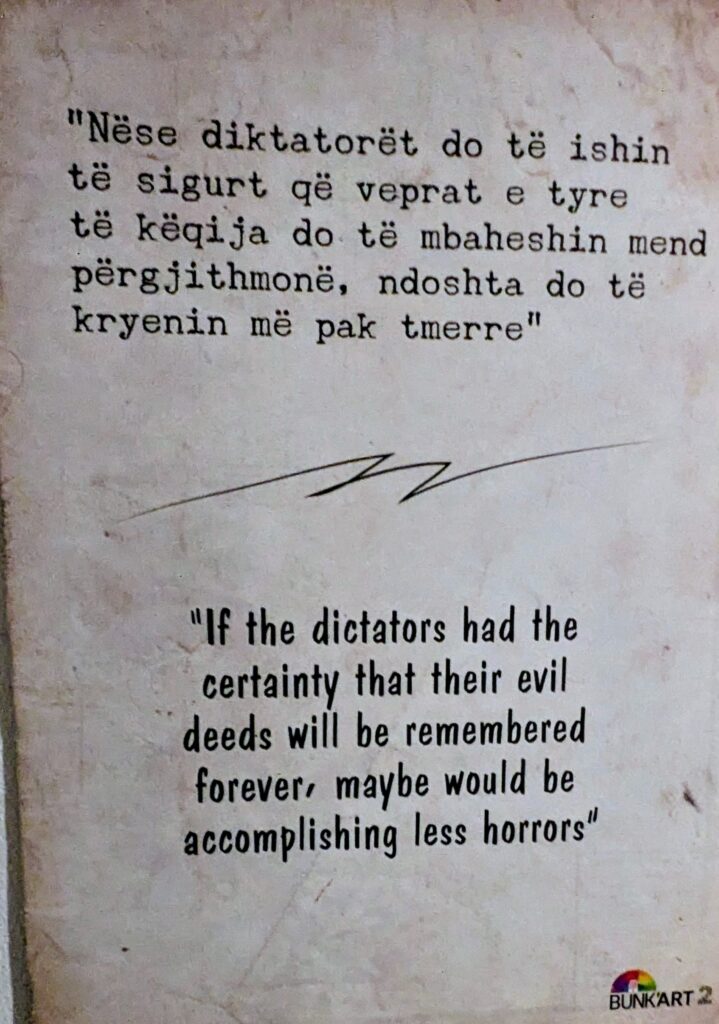

By evening we reached Tirana. In Skanderbeg Square we visited Bunk’Art 2; an exhibition housed in a former nuclear bunker. It documents executions, labour camps, surveillance, and everyday life under dictatorship (if you only have a couple of hours in Tirana, this is the one place you must visit).

It was sobering. If you want to understand what life behind the Iron Curtain actually meant, this is the place.

Afterwards, the contrast was jarring: Christmas lights, mulled wine, families milling around the square. Albania doesn’t shy away from its past, but it doesn’t let it dominate the present either.

Final Thoughts

Albania is stunning, mountains, rivers, coastline, but it is also fragile. Tourism brings money, but also inflation, displacement, and strain. The infrastructure feels provisional. The inequality is visible.

And yet, it’s a country worth seeing, perhaps especially off-season, when the gloss falls away and the underlying reality becomes clearer.

I’m glad I came. I’m not sure I’d return in peak summer. But Albania, in winter, made me think, and that, for me, is always the mark of a worthwhile journey.